|

1) Afghanistan On the soldiers’ shoulders As long as the Afghan people We cry out Those breathing freedom

2) Scrap After us will be neither scrap metal When someone knocks on the door

3) Last Supper Thirteen of us still not released And we the living |

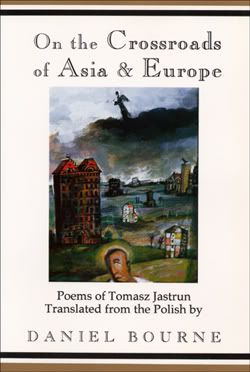

On the crossroads of Asia and Europe 138pp / Paperback / $10.00 ISBN 1-887573-05-4

“A friend and fellow writer, speaking in reference to contemporary poetry, remarked to me not long ago that the true poets are not those in search of something to write about, but those whose subjects have discovered them. I find this confirmed in reading the poems of Tomasz Jastrun.” – John Haines “Here at last we have a generous selection of Tomasz Jastrun’s poems and prose chronicling the disintegration of Poland, and celebrating the unlikely survival of the human spirit. We have Daniel Bourne to thank for guiding these poems into English.” – John Witte, Editor, Northwest Review “Deep gratitude to Daniel Bourne and Salmon Run Press for making available in English the profoundly moving voice of Polish writer, Tomasz Jastrun. This is crucial, empowering work.” – Naomi Shihab Nye

On the Crossroads of Asia and Europe collects the poetry and satirical prose of Polish writer Tomasz Jastrun, winner of the 1983 “S Prize” from Underground Solidarity for his poetry during Poland’s martial law period in the early 1980s.

Daniel Bourne teaches at The College of Wooster (Ohio), where he edits Artful Dodge, a journal of new American writing and literature in translation. Since 1980 he has been a frequent visitor to Poland, including on a 1985-87 Fulbright fellowship for translation work with younger Polish writers. Salmon Run Press is one of only two Native American-Owned Publishing houses in America. Its titles are distributed internationally in the US, Canada, England, and Australia. Each year since 1991, Salmon Run has sponsored the National Poetry Book Award, of which On the Crossroads of Asia and Europe was the selection for 1998.

|

4) Instruments of Crime

In 1984 — not the book but the year — my typewriter was taken during a search of my apartment. But it didn’t happen all at once. Later I even went to retrieve it from Rakowiecki Prison, where it was impounded because the fun-loving, blue-eyed captain in charge of the operation determined that since nothing of importance was found in the search, they must punish me for my perfidious caution by confiscating the tool of my trade. The typewriter was an old Continental, ancient but in perfect shape. I had received it from my father, Mieczslaw Jastrun, who among other things had written on it his book Mickiewicz, a part of the mandatory reading curriculum, during high school. The officers who carried the typewriter away had no idea that they held in their hands the instrument responsible for their required reading once upon a time.

That same day I myself ended up being held for 48 hours in one of the dark and dank cells of the commissariat on Antoni Malczewski Street. Malczewski, alpinist and Romantic poet, on the peak of his wildest dreams would never have imagined that below his street, in such gloomy and smelly cellars, people would be locked up for writing poetry.

“I ran you in because you wrote a poem about me,” my guardian angel at the commissariat had said cheerfully. And with these very words I started a new poem. Writing is such a terrible addiction.

Several months later, without a whole lot of hope, but rather with deep misgivings, I made my way back to Rakowiecki to take up the task again of reclaiming my typewriter. A well-padded officer in charge of complaints led me upstairs past some rooms I knew well, where on the walls the calendars with naked girls proclaimed that even here new times were on the horizon.

There was my typewriter sitting on a desk. Tenderly I stroked her sides. “No, not here,” she warned. “Not in front of them.” I had to write out an affidavit stating that the typewriter was in good condition and that I was here to claim it. Then, right in the doorway, I had a close encounter of the third kind with a short, elderly stubby-fingered man whom I already had the displeasure of meeting from time to time, and ho gave himself out to be the head bookkeeper in charge of keeping track of the sins of the artistic world. Sneering at the my haste to leave so quickly, he declared we needed to have to have little chat in his office before the matter could be completely settled. He advised that I put the typewriter back on the desk and sit down and take a load off my feet. But when it appeared clear that only through the use of force would it be possible to seat me, he reflected for a moment and then said with total politeness, “We’ll let you go ahead and stand.”

I soon learned my poems were a bridgehead in the battle against the People’s authority. And, moreover, an entire staff of specialists had proved that I had used this particular typewriter here to write three poems that had especially entrenched themselves in this bridgehead.

“We ask only one thing,” the officer said, his short fingers clasped together on his belly, “that you give us some sort of affidavit- even an oral one would do” — he threw amicably — “that you will not be writing any future work on this typewriter that would besmudge People’s Poland.” I stood there in silence, not, however, avoiding staring back as he stared at me. After several minutes of this exchange, which seemed like a veritable war of faces from a Gombrowicz novel, he finally cried out, “Why are you looking at me like that? I bet you’re thinking that soon the tables will be turned, but, no way, no way will that ever be!” It’s curious what swirls in some people’s heads on the nights they can’t get to sleep.

My further silence must have been taken for a sign of insolent rebellion, because then I heard that action was indeed going to be taken against me — of course a patent fiction because my case would be covered by the approaching amnesty anyway — but the typewriter itself could still be forfeited as an instrument of crime.

“We are letting you go this time only because we know your family is expecting you.” Then he tore to his feet, which gave me the impression he had just been jerked by a leash. I left without the typewriter and without the affidavit that I was reclaiming it. The only thing had was a feeling of being covered with lice. Soon afterwards I received word that my typewriter was still under investigation.

Unfortunately, the investigation of the typewriter is still going on. Surely it doesn’t have much left it would want to confess. in such a situation I can only admit further that I have a second typewriter at home and that on it I have written other texts that make up the remainder of the bridgehead against People’s Poland. The officers carrying out yet another search of my home even saw it, though this time they didn’t take this dangerous instrument, I suspect because it wasn’t just a matter of the machine being dangerous, not just that at all. Rather, they came just because they wanted to show us again that our apartment doesn’t have doors, that laws can be broken in the blink of another law, that words can be shut inside a jail.

In the margin, I would also like to establish that there had also been left in Solidarity’s Mazowsze Region Headquarters (where I worked and which had been overrun by the authorities at the start of the martial law), a Christmas package for our son, that my wife had left an umbrella and a wicker basket, and that I had left behind a rather handy space heater with a ventilator fan. I’m sorry that in such public times I write about private matters. Still, these private concerns have a more general dimension at the moment. The time has perhaps come for the office of confiscated articles to be converted to an equipment rental agency.

– Gazeta Wyborcza, No. 34, June 23-25, 1989.